Every year we are starting this Holy Week listening to the episode of the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, riding on a donkey and being cheered upon by the crowds of his disciples and followers, all of them fired up by the promise that he might be vindicated as the Messiah, which is why they acclaim him as the king of Israel, the son of David. This scene, which we find in the four gospels, has even been named as the “triumphant entry” into Jerusalem, an understanding that without doubt would have been alien to the mindset of Jesus, who always tried to avoid that the expectations of a messianic leadership could grow around his person.

The events that happened in Jerusalem in the following days, which we also listen to in today’s passion narrative, and which will culminate with his shameful death outside the city walls within just five days from today, are a cruel reminder about the fragile meaning that an enthusiastic crowd may carry: today’s approval will soon turn into deception, and later on into outward rejection, because Jesus is not going to fulfil the expectations of the people who were longing for a political leader who might guide them towards a more prosperous life and turn them into a powerful and respected nation among its neighbors.

The contrast between the episode of the so-called triumphant entry into Jerusalem today, cheered and applauded, and the way Jesus will exit the city carrying the wood of the cross, mocked and spat upon, couldn’t be greater. Only a group of women will remain at his side, knowing that the gospel Jesus preached with his life and his words has to be embraced and understood in the heart of every single person, far from the multitudes who only project upon their leaders their own dreams and ambitions.

Jesus did never allow himself to be fooled by the crowds who were asking for a messianic leadership to make their nation great again, and announced several times that they themselves would end up demanding his death, as it turned out. As followers of Jesus, we should avoid the ever-present temptation throughout history of populism and of yielding to the longings of enthused crowds of diverse political and social signs, always eager of finding leaders who can deliver their own targets and goals. The gospel of Jesus, yesterday, today, and forever, is a path of loving self-giving of one’s own life, which is made real in the encounter with our neighbor, far from the crowds and their wishes and longings, as Jesus himself showed us with his own life.

Happy Easter of Resurrection! Today we are starting the longest of all liturgical seasons, 50 days that offer a unique opportunity to savor and make ours what we have just celebrated. Jesus, alive and present among us, is the reason of our joy; otherwise, our faith would be void.

In this season of Easter we celebrate the great feast of the Love of God, that has been bestowed on us with no merit of our own, as the Gospel of John states clearly: “For this is how God loved the world: he gave his only Son” (John 3, 16). We recognize, as our liturgy points out, what God has done for us, out of love, by offering us salvation in his Son, even in death. Easter is a feast because we celebrate the gift of life that comes from God, and which none of us have merited or achieved of our own.

Our main attitude in this season of Easter and, therefore, in Christian life, has to be gratitude: being and living in thankfulness is a virtue that should define our lives, signaled by Faith, for, while embracing the experience of Easter, we recognize that life is always a gift. This is the very essence of our faith, as the Easter proclamation goes: “Our birth would have been no gain, had we not been redeemed. O wonder of your humble care for us! O love, O charity beyond all telling!”

In this season, more than ever, we celebrate the love of God in our lives. It is only fitting to ask ourselves if the way we live our faith reflects this gratitude for the gift we have received or, if more often, we go back to religious practices where we try to please God with our worship, our piety or even discipline to show him our love. A truly Easterly faith will not try to “gain” God’s love, for redemption can only be understood as the free outpouring of divine love, and the only way to respond to this gift is gratitude, the truly Easterly virtue of Christian life.

Merry christmas! Today we celebrate a unique birth: that of a child, vulnerable and defenseless, who came into this world in total anonymity, unknown to the powerful and important of the society of his time, and who, however, was also born marked by the promise of that would change the course of History, as the angel announced to the shepherds: "Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.” (Luke 2:10-12).

It was they, the irrelevant and poor shepherds, who were the first to visit him in the stable in which he had been born. If we think for a moment about that humble and simple place, which sheltered some involuntary pilgrims displaced by Roman power, we can affirm, without a doubt, that it smelled of sheep, since both the place and those who went to visit it would be impregnated with its smell. In fact, that was the first smell that surrounded the newborn, and that would remain engraved in his memory. Modern science affirms that olfactory memory is the most primitive and also the most emotional of the experiences that we accumulate as memories. A smell and a taste inevitably take us to a remote experience, recorded in our memory, and link us to it.

What do sheep smell like? Whoever knows the countryside, and the life of the shepherds, knows that the sheep smell of sweat and manure, that is, of poverty, and of humanity. The smell of it is not perfumed, nor does it convey the solemnity of incense or the sacred. What's more, he who gets too close to the sheep, and assumes responsibility for herding, not only ends up smelling like them, but also becomes filled with ticks, their inevitable parasites. In today's Feast we see how Jesus was born in a manger, in a stable, and thus he came to be impregnated with the smell that both animals give off, as well as the humanity that accompanies them, signified by shepherds. A penetrating smell that generates rejection, while defining a commitment to the poor and marginalized.

Nowadays, we can add, the sheep smell of drugs, migrants, and exclusion. It is the smell of those who fight to survive on the periphery of societies, and have been deprived of their dignity, as were the shepherds in the Christmas story. That is the first smell that Jesus knew. And it is the smell of Christmas. Pope Francis likes to ask shepherds to smell like sheep. Christmas teaches us that this smell was assumed from birth by the child we adore, a smell that forces closeness and solidarity with the suffering who multiply around us. It is only in this exchange with the sheep and their shepherds that we can come to understand the unexpected Savior who came to fully assume all of our humanity in order to share with us his divinity.

At the heart of the Holy Week we encounter Holy Thursday, a day defined by the celebration of the paschal supper of Jesus with his disciples, and the promulgation of the Commandment of Love. This is, no doubt, a heartbreaking day, in which the drama that is going to unfold in the coming days is being anticipated.

Today’s liturgy revolves around Memory: the reading of the book of Exodus remembers the salvific action of God in Egypt; Saint Paul in his letter remembers the last supper of Jesus; and Saint John in the Gospel remembers the washing of the feet and the example of service that Jesus established with his disciples. The Eucharist is therefore instituted as a remembrance, underlined by the following words: “Do this in memory of me”.

Those of us who are taking part today and any other day in a eucharistic celebration are being summoned to reenact “this”, which is no other thing than a life devoted to the service of our neighbor, serving, and not being served, the life of the one who “loved us to the end”, as today’s Gospel tells us.

The last supper defines therefore Love as Service, not as Sacrifice, for the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross was given once and for all and does not need repetition. True Christian worship is not, as one may think, the celebration of rites and sacraments, but the loving care of our neighbor which is being carried out as gratitude for the Love received. “If I, therefore, the master and teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet. I have given you a model to follow, so that as I have done for you, you should also do.”

The most powerful homily of Jesus are his actions, beyond his words, for he preaches with his deeds: the washing of the feet shows us the way towards evangelizing, which is living in service and preaching with our example, with prophetic gestures, full of the tenderness and humility that this passage in the Gospel of John depicts.

This Holy Thursday we are invited to commit with the true Christian worship: serving our neighbor, not in the temple, nor at the altar, but kneeling in front of those who walk with us the journey of life.

In the contemporary world human life is, without a doubt, marked by events and experiences that occur in an unstoppable sequence from the beginning to the end of it. As if it were an obstacle course, or a carousel, we jump from one stage to the next, living each one of them intensely: the announcement of a new life on the way, its birth, its initial development, the achievement of his or her personal or academic achievements, the participation in significant social events, etc. The immediacy provided by our media turn life into a collection of moments that we can share in front of our social circle as we are experiencing them, thus building a life itinerary dotted with events that we want to remember.

However, these stages, or vital events, hide the valleys or gaps that lie between one event and the next, and in which apparently not much happens: the days that resemble the previous or next day, the encounters and conversations which are predictable and ordinary, the daily effort to carry out a commitment or a personal (or familiar, or collective) project. The vast majority of our days, in fact, are not marked by an event. Instead, they are simply part of a process. There is little or nothing remarkable in any given day within a process of personal maturation, healing, learning, or overcoming. They are part of a path, of an itinerary that has a more or less distant destination as its goal, and to which a person can only get closer through multiple days that are very similar to each other.

The pilgrims of the past knew they were on the way, living the innumerable steps of their itinerary without the rush or anxiety of someone who needs to be able to announce that he has already achieved a new accomplishment in his life. As if it were a pilgrimage, the stages of a process of human development are only significant as a whole. Seen one by one, they are not enough to convey the immediate satisfaction to which modern life aspires, eager for events that seek to fill the dreams and vital needs. Learning to live on the road implies understanding life as a slow process, one that requires patience, and giving up the necessity to present immediate results and experiences to others.

Modern human beings lack this sense of time, and of the rhythms with which nature itself impregnates their daily living in a natural environment. The original peoples who still live subject to nature are well aware of the patience of the farmer or the shepherd, whose days are practically the same as each other, but little by little they are reaching fruits and results. Jesus of Nazareth, a man who grew up and was educated in the rural world, showed the wisdom of one who knows that life is a journey, rather than a sequence of events: "The reign of God is like a mustard seed which someone took and sowed in his field. It is the smallest of all seeds, yet when full-grown it is the largest of all plants. It becomes a big shrub, so that birds come and make their nests in its branches.” He also told them another parable: "The reign of God is like yeast which a woman took and kneaded into three measures of flour. Eventually the whole mass of dough began to rise." (Matthew 13:31-33)

In contrast to this ancient wisdom of the rural world, our time is characterized by the immediacy of events, information, and communications. Yet, life is not a chain of events, but a process, slow and calm, in which the path is oftentimes more significant than the destination. To be able to make this path of life in peace, it is necessary to live each stage with its own flavor, without wanting to accelerate or advance events.

A life that is open to the fruits that ripen in due time, and to the yeast that gradually ferments the dough invisibly, will be a life that does not yearn for immediate results, but trusts in the chosen itinerary, and savors each one of its stages.

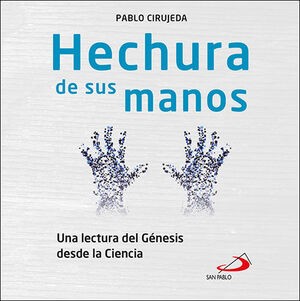

We are pleased to share with you the recent publication of “Hechura de sus manos,” (translated to English: “The Work of His Hands”), a book by Pablo Cirujeda, member of the CSP and regular collaborator in this blog. Published by Editorial San Pablo in Madrid, the book contains a series of reflections in which the author puts the stories of the book of Genesis in dialogue with our modern science.

On the back cover we read: “Starting from Genesis, Pablo Cirujeda, priest and physician, presents some brief reflections that are serene and conciliatory, in which he searches for, and finds, that which unites human beings with one another; and with God. His words demonstrate that time, the creative capacity, and of course, love, along with other themes, weave together that indissoluble material that, stitch by stitch, come to make up everything.”

A book that is both enjoyable, and necessary. Congratulations Pablo!

The Easter season is the longest of all the seasons of the Church, fifty days dedicated to the contemplation and meditation of the experience lived by the disciples of Jesus, men and women who followed him and who believed in his preaching, discovering the Jesus himself resurrected after his death on the cross. During this time, they got to know him and recognized him in different ways, always with the initial doubt about his identity, since it was the same Jesus with whom they had walked and eaten―and at the same time it was a new and different Jesus.

We Christians profess that Jesus defeated death and reached the definitive life of God in which he remains eternally. Alive, it manifested itself to his disciples, and alive they experienced it in the different encounters that the Gospels describe. Alive, but different… because life changes, always, and it changes even more in those who have experienced death. Nature clearly shows us that all living beings are subject to permanent change throughout their life cycle, and that we can observe and recognize the transformation that occurs in the natural world around us, which was mentioned so many times by the Jesus himself in his parables, such as those of the sower, of the vineyard, or of the fig tree and its fruits.

Saint Paul also speaks of the transformation that entails the transition between life and death, using an image of nature: “The seed you sow does not germinate unless it dies. When you sow, you do not sow the full-blown plant, but a kernel of wheat or some other grain” (1 Corinthians, 15:36-37). Life, therefore, is characterized by change; it is what does not change and remains the same that is dead. In daily, everyday life, the changes are perhaps less striking, but they are always present, because in human relationships, for example, such as friendships, we learn that everything changes over time: relationships are strengthened and developed, while others decrease or disappear.

Love, which is life at its best, confirms this dynamic of transformation: love that is alive is constantly changing. Pope Francis says it very well in his letter on the joy of loving: “A love that fails to grow is at risk.” (Amoris Laetitia, 134). Love grows or decreases, but like all living reality, it is subject to constant change, it does not remain the same by itself, and it needs to be nurtured in order to evolve.

The resurrection, therefore, is the manifestation of a life that will continue to grow without limits, and that will take on multiple forms, because in its development it will never stop changing. The encounter with the risen Jesus takes as many forms as there are people who have experienced it, and it will always be new and different, because He is alive. For the followers of Jesus, assuming his resurrection is to live embracing the permanent change in our own lives, discarding the old, open to the permanent novelty of God. “Clothe yourselves, therefore, with the new man” (Ephesians 4:24), exhorts Saint Paul several times to his followers.

A resurrected Christian community, and a resurrected believer, must distinguish themselves by being alive, that is, constantly renewing and changing, thus responding to the needs of their own life and that of the world around them. Saint John Henry Newman said with great precision: “In a superior world it can be otherwise; but here below, to live is to change, and to be perfect is to changed many times.” To live is to change—and by changing, we manifest the life that beats within each one of us. The fear and resistance to change that people, institutions and societies express so vehemently is, ultimately, a fear of life itself, of being alive. Jesus overcame that fear forever, and with his resurrection he taught his disciples, and he teaches us, to live changing, many times.

On this day the Church is focusing on the striking and powerful narrative of the Passion according to St. John. Listening to the events that eventually led to the death on a cross of Jesus, it is unavoidable that we reflect today on human suffering, to which he submitted himself.

Suffering and death are part and parcel of human life, even though we all would like to avoid them both especially for our loved ones and for ourselves. Disease, injustice, envy or rivalries will, sooner or later, bring about suffering to ourselves or to those around us. Once we meet these realities, our trust in God will be challenged, again and again.

This is why the story of the passion of Jesus which we read today touches our hearts in a very personal way, because it enshrines everything: in it, we find scenes of goodness, tenderness, friendship and solidarity, as well as others that are marked by treason, lies, violence and death. The full scope of human experience is represented in the Passion narrative, starting from the positive all the way to the darkest moments. We can surely state that Jesus transitioned through the whole of human condition.

At the same time, Jesus is able to merge this great variety of experiences into a single life project, and to offer it to the Father, both the joyous events, as well as the undesirable ones. He does not store up grudges and accepts the opposites and contradictions of his own life trusting fully in the will of the Father. Jesus makes the words of the psalm 30 his own, as he knew them by heart: “In you, o Lord, I take refuge, let me never be put to shame. Into your hands I commend my spirit; you will redeem me, o Lord, o faithful God. (…) My trust is in you, o Lord. You are my God, in your hands is my destiny.”

The questions haunting Jesus on the eve of his passion, as they do to any of us facing similar situations, are the same: who will have the final word in the face of suffering, injustice, sickness, and death? Is the love of God really able to defeat evil, pain, and humiliation? Today we see that Jesus’ answer is the answer of faith, that is, of an unbreakable confidence in God that goes beyond understanding what is happening. “My trust is in you, o Lord …” When I am alone, my trust is in you. When I am a victim of injustice, my trust is in you. When my body reaches its limits, my trust is in you …

The way Jesus todays surrenders to the Father, in silence and complete confidence, deeply connects with our own human condition, since we necessarily identify with some of the experiences Jesus went through in his passion. Today we are called to renew our faith with him, which can be summarized with these simple words: My trust is in you, o Lord.

Reviewing experiences of different members of the Community of Saint Paul this past Holy Week, we reproduce here this testimony that Pablo Cirujeda sends from Mexico City.

In the context of the Holy Week celebrations that we organize in the Rectoría del Rosario, in Mexico City, with the support of three other parishes of the deanery, we had the idea of organizing a different footwashing this past Holy Thursday.

For a year we have been cooking and delivering food to the unemployed and homeless population that congregates around the bus terminal and Metro Observatorio stop, right on the parish boundary. This activity takes place every Tuesday and Thursday, and currently we have already been able to share more than 15,000 hot meals.

We planned to carry out a foot washing for Holy Thursday after the delivery of food to all the people who would like to receive this risky and humble gesture of Jesus. After a year walking with this marginal population, there are countless stories and encounters that our pastoral team has treasured with them: stories of violence, marginalization, hope, addictions, struggle, migration...

However, on a daily basis we witness the scarcity in which these people find themselves, and that on many occasions they have asked us for support with clothes, shoes or medicines. How to wash their feet and see that those same feet return to some torn and worn shoes? So, during the Lenten season we collected new or used shoes in good condition among many volunteers and donors, and also socks to complete each pair.

Then, on Holy Thursday, after the delivery of the usual 250 meals at noon, we invited those who had received the meal to have their feet washed by one of the four priests present, or by some volunteers from this community project. One by one they went through this simple ritual, after which we were able to give them a new pair of shoes and new socks.

Thanks to the support of a large group of volunteers from the four parishes that we collaborate with in this project, including a youth choir, the ceremony was carried out with order and great emotion on the part of the people who were presented with their new shoes.

This Holy Thursday, despite the needs generated by the pandemic, we were able to share a little solidarity with some of those most affected by the lack of employment and a decent home.

In an article published in the April edition of Vida Nueva, a Catholic magazine in Spain, Pope Francis wrote of the need and urgency of creating a “Plan for Resurrection.” Making reference to Mary Magdalene and the other Mary encountering the empty tomb, with the large stone rolled aside, the pope says that we find ourselves in a situation where we may be asking ourselves the same question that the women asked when they were on their way to the tomb: “Who will roll the stone from the tomb,” for us? (Mk 16:3). Francis reflects that “the heaviness of the stone in front of the tomb that seems to impose itself before the future, and that threatens, with its call to realism, to entomb all hope.” But the women “in the face of doubts, suffering, perplexity before the situation, and even fear ... were able to move forward and not be paralyzed by what was happening.”

Thus, they arrive at the tomb “in the midst of their occupations and worries,” and they do not realize that "the stone had already been rolled over." “Only a shocking news was able to break the circle that impeded them from seeing that the stone had already been rolled away”: He is not here. He is risen.

Pope Francis proposes that the international crises presented by the novo corona virus is a “favorable time” to have new creativity regarding the possibilities within our social structures and organizations. Illumined by the Gospel and inspired by the Holy Spirit, we can see in this historic moment the importance of “uniting the whole of the human family in the search of a sustainable integral development,” (citing himself in Laudato Sí, n. 13). Something we have learned in this pandemic is that, “no one is saved alone.” While this is reflected in the Scriptures and in the teachings of the Church, we are living it out in a direct way today, with the need for communal efforts in order to slow the spread of COVID-19.

It is precisely in this time of coming to terms with a “new-normal” that Francis sees the opportunity for us to be intentional with regard to how we relate to one another and how to build a world economy and society that overcomes what Francis deems the “globalization of indifference.” This is to say, we can be intentional about what the “new-normal is,” and instead of simply going back to what was, to rather have a socio-economic network that is based on social and religious values that protect the dignity of the human person, instead of seeing a person as something to be exploited as a laborer, or even, consumer.

Jesus gives clear guidance of how to build up such a society in the values presented in the Beatitudes. In May, Pablo Cirujeda, priest of the CSP working in Nuestra Señora del Rosario Parish in Mexico City, reflected in this blog on the Beatitudes as “a Roadmap in Times of the Pandemic.” He said there: “The Beatitudes do not contain an empty promise of future comfort, nor an invitation to resignation in the face of present suffering. Rather, they are an active invitation to work to remedy the causes of human suffering.”

International news has covered how the pandemic has hit Mexico very hard, especially in the capital. Members of the CSP present there (Pablo, Sarah and Angels) have been busy aiding families in the parish and in our San José Center.

An uplifting and beautiful addition to these efforts is the mural based on the Beatitudes that the parish has had painted on one of its walls. “I had actually been planning on the mural project since September,” said Pablo. “But the artist I was working with fell through. I was just now able to find a good fit for the project, and I think it was perfect timing, to have this done in the midst of the crisis.”

We have a once in a lifetime, perhaps even once in a century, opportunity to rebuild, to resurrect as a stronger, more just society after the pandemic. The roadmap is, as it always has been, the values of hope and justice presented in the Beatitudes. “I hope,” said Pope Francis of our current moment, “that we discover ourselves with the necessary antibodies of justice, charity (love) and solidarity.”

You can see a video of the painting of the mural in Mexico here: https://youtu.be/-aarTHImiLM. If you’d like to support the work on the CSP in our efforts related to the pandemic, see https://www.csp-covid19.com.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” (Matthew 5:3-10)

These words of Jesus, so vividly engraved in the memory of his disciples that walked with him, and transmitted up to our times, have been considered by many as the essential text of the Christian message, its most correct synthesis, capable of challenging the life of any person and to gain relevance in the face of any challenge or historical situation.

Undoubtedly, the Beatitudes today acquire their full meaning again in the face of the situation of the pandemic that we are experiencing and is still unfolding before our eyes in an uncertain way, without us being able to know the future that is taking place, the famous "new normality” towards which we are heading globally and also locally and personally. In each of our realities we are witnessing so many heartbreaking situations of poverty, crying and despair... along with countless testimonies of mercy and commitment to the most vulnerable.

If we reread the words of Jesus carefully we will see that they are clearly grouped: the first four beatitudes speak of passive suffering (that of the poor, those who cry, those who suffer...) to which so many people are subjected today, trapped by the uncertainties in health, society and the economy. The following four also mention those who work to remedy that same suffering (the merciful, the clean-hearted, those who work for peace and justice ...). We see, therefore, that Jesus addresses both those who are overwhelmed and powerless in the face of present suffering, as well as those who have the possibility of facing it and committing themselves to a more just and equitable future.

The Beatitudes do not contain an empty promise of future comfort, nor an invitation to resignation in the face of present suffering. Rather, they are an active invitation to work to remedy the causes of human suffering, here and now, and in all historical circumstances, thus defining the true itinerary of the Christian life. The kingdom of heaven that they announce is already present among us, and it can and should be built with the commitment for peace and justice, from the mercy and the cleanliness of heart of those who know how to be moved to compassion in the presence of the brother or sister who cries of helplessness and rage in the face of the loss of a loved one, and it is going hungry for having been left without work and without means to support his family and to pay the rent.

On the occasion of the Extraordinary Mission Month convened by Pope Francis for October 2019, the Archdiocese of Mexico proposed that all parishes join in this initiative through a “megamission” to meet the people most in need of joy and hope in this great city.

In the Rectory of Our Lady of the Rosary, directed by Pablo Cirujeda, of the Community of Saint Paul, all parish groups participated with a weekend dedicated to the sick and the elderly confined to their homes by their chronic conditions. As many as seventy children of the children’s catechesis program, their catechists and parents, as well as other pastoral agents—members of the liturgy team, family ministries and other parishioners—set out to walk the streets of the neighborhoods that are form the parish territory, visiting about forty people who received, with some surprise, the fact that the parish community was approaching their particular situation to listen and accompany them, and in some cases assist in their needs, such as cleaning the house or getting warm clothes.

As a result of this initiative we will assume the commitment to continue visiting those people who have requested it, to offer them company, bring them communion, and give them the opportunity to continue being part of the parish despite the limitations imposed by their diseases .

We all enjoyed this weekend of parish mission, but especially the youngest along with the oldest, discovering a way to be together despite their differences and the distance between generations.

The CSP is present in Mexico City through two different pastoral projects: on the one hand, in the south of the city we coordinate the Community Center for Child Development “San José”, in which 122 children under 6 years of age receive comprehensive attention every day in the crucial stage of early childhood. On the other hand, in the west of the great city we support pastoral and social work in a popular neighborhood of working population.

After having worked for five years as an associate pastor in this second pastoral area of the archdiocese, Pablo Cirujeda was recently appointed rector of the Rectory of Our Lady of the Rosary. As head of this parish, he will serve a population of about six thousand people, mostly from humble and low-income families. In addition to the coordination of the different pastoral programs (children's catechesis, pastoral care of the sick, celebration of the sacraments, etc.) the parish is currently also opening spaces for community development, such as craft workshops for children and young people, physical activation for older adults, and a Therapeutic listening center. At the same time, Pablo is establishing a collaboration with other institutions and social agents in the area to start a job training program for young people.

This new pastoral challenge adds to the efforts of the CSP in Mexico, so that its commitments address an integral evangelization of the person, understanding the pastoral as a path that encompasses all personal, family, and social dimensions of the human being.

Today, Ash Wednesday, we begin Lent, and we begin this time hearing a call that describes in a clear and convincing way the ideal of Jesus with reference to solidarity with those in need. “When you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right is doing, so that your alms may be done in secret. And your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you.”

Proximity to the poor and commitment to alleviating human suffering form part of the essence of Christian thought. Pope Francis continues to emphasize this with words and closeness to the “the least of our brothers”, the ones discarded by the society of success in which we live. The commitment to the poor must be fulfilled through tangible and real actions on behalf of our fellow man, the people around us, and in the world, who suffer from material and spiritual scarcities. We must go further than a theoretical discussion of good intentions.

For years, we, the Community of Saint Paul, have been promoting volunteer work as well as accepting much needed monetary donations in order to be able to accomplish the aid and development projects to which we are committed in Bolivia, Colombia, Mexico, the Dominican Republic and Ethiopia. Volunteer groups come to collaborate in different ways with us: some volunteers work in professional capacities, such as doctors, ophthalmologists and educators. Others bring material goods for those in this world who have the least...the people who fall in the ever widening social gap between the rich and the poor.

However, it is necessary to remind ourselves again and again of Jesus’ teaching that our left hand does not know what our right hand is doing. In a world that relies heavily on social media for communication and measuring results, many people and charitable institutions feel pressured to show what they have achieved as a result of their collaboration or gifts. Photo exhibitions, testimonials and data related to charitable actions generate satisfaction among volunteers and donors for having been able to contribute to change. They calm wounded consciences faced with the flagrant social injustices which we all witness.

As we begin Lent, Jesus challenges us to do good, but... to do it silently, in a discreet way, even anonymously, without the need to show anyone the results that we have achieved. Free selfless assistance doesn’t only benefit the people whom we help. It also teaches us to live the values of humility and discretion. We learn to distance ourselves from the limelight in a world accustomed to exhibiting and recognizing every action that is undertaken, including charitable initiatives. Let’s think about the challenge Jesus presents to us today: can my right hand live without knowing what the left one is doing?

One more year, we embark again in the path of Advent, a path of hope, but above all of joy for the feast that is about to come. Unlike Lent, Advent is not a time of penance, but of preparation for the first great event celebrated by the Church in its annual calendar: the feast of God’s closeness, who lowers himself to embrace the human condition in history, offer his solidarity, and elevate us to his own dignity.

As we would do before any other great event in our lives, we cannot sit down and just wait, doing nothing, to see what happens next. Advent is a time of active preparation, which demands our commitment and requires us to clear any obstacle so that the feast can be celebrated in the best possible conditions. We will hear these days the prophets speak of the need to «fill up the valleys and lower the hills», and thus prepare the ways to the Lord.

«The one who waits, despairs» is the logic of the world, of those who limit themselves to receiving, with resignation, what life can offer them, but without getting involved in the events that happen around them. Christian hope, on the other hand, becomes the impulse to go out to transform the world, so that the advent of God will find us ready and awake, yearning for a better world.

The Community of Saint Paul, small as it is, takes part in the work carried out by the Church throughout the world, to transform the social and even the economic environment as leaven in the flour, making a difference in the fields of human development, education, health, human rights and the dignity of others, especially of those who suffer poverty and exclusion. It is the task to help clear, one by one, the obstacles that separate us from God’s plan for humanity.

With the renewed joy and strength of those who know that a better future is about to come, we intend to continue working to break down walls, build bridges and heal wounds in a world still full of divisions, and invite all our readers and friends to join us in this Advent project, because we are not willing to accept, just like that, the “valleys and hills” of history that surround us.

Today, we begin the journey of Lent: 40 days focused on the task of preparing ourselves for the annual Christian feast of Easter. Today, Ash Wednesday, we receive a sign upon our forehead: a bit of ash that reminds us that, according to the ancient story from Genesis, “you are dust and to dust you shall return.” (Genesis 3:19)

This phrase could sound somewhat sad or defeatist, and even antiquated. It reminds us of the biblical punishment to which Adam and Eve were condemned after daring to eat of the fruit from the tree of Good and Evil. We must admit it: none of us like to be reminded that, sooner or later, we will return to the earth from which we came – this is an inevitable destiny for all human beings.

However, today’s ceremony carries a positive message as well. Upon recognizing that we are not eternal, that we cannot avoid the final destiny of our lives, we recognize our contingency, our finiteness, before God, the only absolute.

All human beings tend to “absolutize” someone or something: sometimes we absolutize ourselves, other times we do it to other persons; we absolutize our social role, our activities… Today we remember that we are finite creatures created by an infinite God. The ash on our heads helps us to avoid falling into the narcissistic thinking that no one, nor anything, can limit me, that I am an eternal being.

“You are dust, and to dust you will return”: God reminds Adam and Eve that they – us – are finite creatures, that we are not gods. This is not bad news, for the recognition of our finiteness liberates us to live with joy in the present, the now, instead of selling ourselves to a future that is so often imaginary, for which we are sometimes willing to sacrifice the present, instead of valuing the today and now as a unrepeatable gift that deserves to be lived intensely with full joy and liberty.

Pablo Cirujeda

The question about human nature has been haunting humankind for long, and different authors have defined human nature in different ways. Some have argued that human beings are unique because of their spiritual dimension or soul, which makes them different from all other created beings on earth, being “capable of knowing and loving its Creator” (Gaudium et Spes, 12). Others have said that what makes us human is our ability to overcome and subdue nature: the invention of fire, clothing, agriculture, or medicine would all point to the fact that our distinguishing feature is this capacity to transform and adapt our environment to our own advantage.

St. Thomas of Aquinas once wrote that the nature of human beings is their reason, that is, our ability to think individually and to not just follow predictable instincts or behaviors. Our human nature, therefore, would urge us to use reason while making choices and not just allowing biology or the laws of nature to have it according to their own ways. Scripture tells us that human beings have been entrusted as stewards of creation in order to govern it with our rational abilities. Nature and all it contains would be at our service, not us at the service of nature.

Be it as it may, what these different approaches all have in common is acknowledging that human beings are biological by nature, but cannot be defined by biology alone. “Natural” does not simply mean “biological”. This difference, I believe, is at the heart of many debates when it comes to making choices that want to be respectful with the laws of nature.

Generally speaking, we usually do not consider altering biological events in food production, for example, as acting against nature: most of our food products, considered natural, are the result of manipulation and processing, either because they originate from transgenic seeds, or because they have been pasteurized, flavored or otherwise changed and adapted to better suit our needs. Likewise, we accept the use of energy to make our lives easier, as much as we applaud every new medical discovery that enables us to fight aging and disease more effectively.

But on the other hand, when it comes to matters concerning human ethics, we oftentimes refer to “natural law” in order to limit our choices: whatever challenges the “natural” order of things, from a biological perspective, now seems to be an aggression against creation. We seemingly have no problem in benefitting from hip replacement surgery, but claim that the process of dying should be “natural”, until the end! (Luckily, what we call natural death is full of human interference that aids the person to face this process in a more humane way.)

Emmanuel Mounier, a French philosopher of the 20th Century, believed that human nature is defined precisely by our ability to subdue nature through artificial means. For us human beings, it is only natural to interfere with the laws of nature, and thus make our life and our world more humane, rational and bearable. If we were to live a life just following the demands of our biological self and environment, that life would be extremely painful!

So, where do we draw the line? How far can we go in using artificial means to dignify human life assisted by our reason? I believe that any human action that respects life and helps us to achieve our mission of building a better world for those who will follow us is morally justified, because human nature is at its best when it challenges biology through reason to uphold the dignity of every human being.

Pablo Cirujeda

The quest for ownership – be it financial means, property, housing, or else – is without doubt a major driving force for many of our human activities. All through life, and rightly so, we strive to attain a certain level of material wealth that may enable us not to worry too much about tomorrow, to provide for us and for those under our care and to meet our needs and responsibilities.

Jesus in the Gospels does not reject the idea of property or ownership as such. His friend Martha, for example, owns a house, while others own fishing boats or other commodities. Jesus repeatedly is welcome to dine at the house of people who have the means necessary to offer a meal to a large group of people, and he does not challenge them on that. To his disciples, nevertheless, he suggests other priorities: leaving property and possessions behind in order to be entirely free to join him in the building of the Kingdom of God.

The teachings of the Church, 2.000 years later, continue to consider private property as morally acceptable. It is only logical that families need to own and use material means to provide for their own, secure their future and be part of society. As we know, the practice of some of the early Christians in Jerusalem, who sold all “their possessions and goods and distributed them to all” (Acts 4:44-45) did not last very long! Paul in his letters calls for an equal distribution of means in his communities, but does not suggest to ordinary Christians to sell “all you have and distribute to the poor” as Jesus had asked the “very rich” man in the Gospel (Luke 19:18-23).

On the other hand, Christian teaching does not endorse unlimited ownership. The Lord’s prayer already asks for “our daily bread” as an image of what we need to get through the day. What Jesus clearly rejects is the accumulation of wealth without limits and for private benefit only, as described in the parable of the rich landowner who wants “to lay up treasure for himself” by building larger barns in order to “have ample goods laid up for many years” (Luke 1:16-21). God himself, in the story, calls him a fool!

Ownership and possessions are means to an end: to be able to provide for all and thus meet our responsibilities as members of the human family. They are gifts to be shared with others. Inasmuch as we may have earned our wealth, we have not earned the right to use it as we please. A false sense of entitlement moved the rich man in the parable to store up treasure just for himself and his own pleasure. Jesus reminds us that we are all stewards of our possessions, and most of all, stewards of the greatest of gifts: our own life. A life not shared with others will be a life wasted; in the same way, possessions not shared with others will be wealth lost, not earned.

Jesus’s invitation is clear: it is by sharing that our gifts are multiplied, so that we may become “rich toward God”.